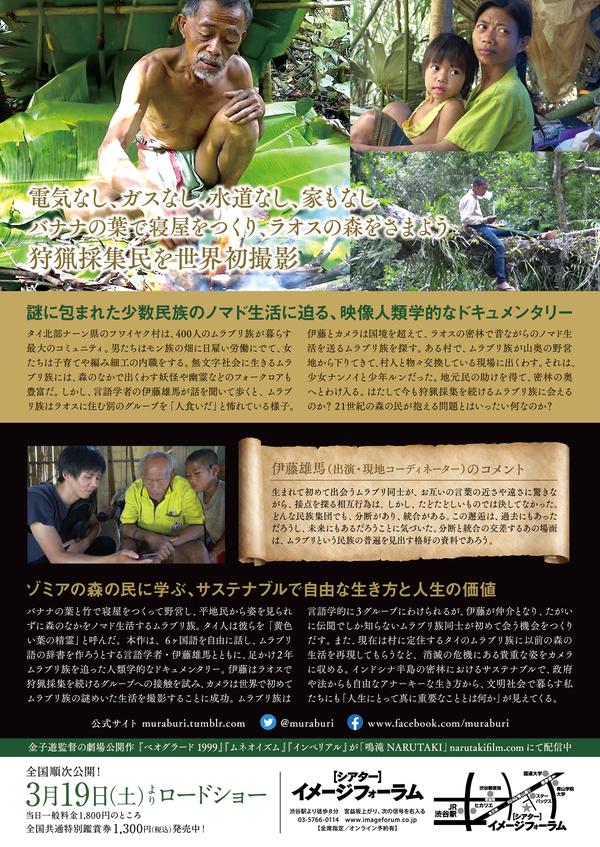

“Mori no Muraburi” Director Yu Kaneko Official Interview – A documentary film on visual anthropology that pursues sustainable living

Muraburi, a minority ethnic group of only about 400 people, live in the mountainous areas of northern Thailand and western Laos and live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The documentary film "Mlabri in the Woods", which captures their mysterious appearance, will be released on Saturday, March 19, 2022 at the Theater Image Forum and other locations throughout Japan. It will be published sequentially.

What the Lao Forest People Teach Us

An unprecedented adventure in which a Japanese linguist opens up the possibilities of visual anthropology to bring harmony to the Mulaburi tribe, who hate each other through the cannibal legend, through the power of dialogue!

The lives of the Muraburi tribe, who make camps out of banana leaves and bamboo and roam the forest without being seen by the plainspeople. The Thais called them "yellow leaf spirits".

This work is a documentary following the Muraburi people for two years together with Yuma Ito, a linguist who speaks six languages freely and collects the vocabulary of the Muraburi language, which has no letters. Ito attempted to contact a hunter-gatherer group in Laos, and for the first time in the world, succeeded in filming the mysterious life of the Muraburi people. It turns out that the Mraburi are linguistically divided into three groups, creating an opportunity for different Mraburi in Thailand who have only heard of each other to meet each other for the first time. In addition, I asked one of the Mulaburi tribesmen from Thailand, who now live in the village, to recreate the way they used to live in the forest.

By looking at an anarchic way of life that is sustainable and free from the government in the jungles of the Indochina peninsula, we, who live in a civilized society, can see "what is truly important."

On the 19th of March (Saturday), a Japanese visual anthropology documentary commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 1922 documentary film "Nanouk of the Far North," which recorded the culture and customs of the Inuit living in northern Canada. From April 8th, it will be released at theater image forum in Shibuya, okayama marumusibi from April 8th, theater seven in Osaka, Kyoto cinema, and motomachi movie theater in Kobe.

Twice a day at Theater Image Forum in Shibuya, at 10:45 and 17:30. A talk event has been decided after the screening on the following schedule. (Additional talk events will be announced on the official SNS.)

-3/19 (Sat) 10:45 episode Yuma Ito (appearance), Kaneko Yu (director)-3/20 (Sunday) 10:45 episode Toranosuke Aizawa (kuzoku/film director/screenwriter) )-3/21 (Mon/Holiday) 10:45 session Hideki Sekine (Author of “Be a Jomon Man!”)-3/26 (Sat) 10:45 time Katsumi Okuno (Cultural anthropologist)-3/27 (Sun) 10:45 Shinji Miyadai (Sociologist) - 4/3 (Sun) 10:45 Ryuta Imafuku (Cultural anthropologist)

----

Ahead of next week's release, we have received an official interview with director Yu Kaneko.

Q. Mr. Kaneko, you have been involved in various activities.

Basically, I'm a writer, a book writer, a critic and a folklorist. On the other hand, I have continued to shoot video works, mainly documentaries, as work and personal creations. Come to think of it, I started shooting in 16mm in 1998 when I was a student, and then shot in 8mm for 10 years until 2008. , Amami Oshima, Kikaijima, Tokunoshima, Jordan, and Iraq. I became aware of visual anthropology around the time I shot anthropological images in Palestine in 2012 and in the Western Himalayas and Micronesia in 2014. However, even if such a short film was completed, it was screened at a film festival, shown as a material video at talk events and university classes, and then distributed on the web. However, when I heard that the life of the Muraburi tribe in Laos had not yet been filmed by anyone, I felt the need to make a feature-length documentary.

Q.What made you interested in the Muraburi tribe?

For one thing, I watched movies such as "Tropical Maladi" and "Uncle Boonmee's Forest" directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. I've been to Thailand several times, but I've become interested in the peas (spirits) and folk beliefs of Isan (Northeast Thailand). The Muraburi tribe, people of the forest, lived in the forests of northern Thailand and were called spirits. I have been interested in cultural anthropology and folklore since I was young, and I read the translation of The Spirit of the Yellow Leaf by the Austrian ethnologist Bernadzig. In recent years, he has often conducted fieldwork with ethnic minorities living in the Zomia (mountainous region) from Yunnan Province to the Indochina Peninsula and northeastern India, and he also traveled to that area in the 1930s. From his book, I learned about the Muraburi tribe, who lived as hunters and gatherers in the forest and were half-naked and nomadic.

Q. Please tell us how you met Yuma Ito, a linguist. How did you feel when we met?

I received a fellowship from the Japan Foundation's Asia Center, so I was able to do some expensive fieldwork from February to March 2017, where I could hire an interpreter/guide and a driver. There is a movie called "Mountain People" (79), directed by Thai director Wichit Kunawut, in which Zomian ethnic minorities such as the Akha, Lahu, and Yao live from northern Thailand to Shan State in Myanmar. The traditional way of life is depicted vividly. In order to deepen my research on folklore with that film as an opportunity, I traveled to the mountains to investigate the religious rituals and beliefs of the animistic cosmology and shamanism of the mountain people. Along the way, I went to Nan Province in northern Thailand, and searched for the Mulaburi tribe, whom I knew only from Bernadzik's books, but whose actual location I didn't know. Luckily, I met a middle-aged woman from a Thai travel agency who knew the village of Muraburi. Then, I met Mr. Yuma Ito, who was doing language research as a live-in in Huayak Village, where the Muraburi people on the Thai side live a settled life, and we hit it off. At that time, I also visited a school for the Muraburi tribe, interviewed elders and grandmothers about their life in the forest in the past, and had them recreate in front of my camera how to make a bed out of banana leaves and bamboo. As a result, I made a short film called "Yellow Leaf Spirit" (17). Unlike the surrounding minority groups who are agricultural peoples, the Muraburi people on the Thai side were hunter-gatherers until a few decades ago, and I was very interested in them.

Q. I think that meeting Mr. Yuma Ito was a big part of the production of this work.

It is true that I was in charge of all the filming and editing, and I was the one who asked the questions for the interview and who did what I wanted them to do, in a documentary-like "guidance", Yuma Ito. I consider you to be a co-creator as well. That is to say, when we first met in Huiak village in Thailand, Ito-san had to ask me, "I want to meet two muraburi who hate each other." I guess. What was even more important was that when the main filming took place in 2018, Mr. Ito had already been going to Huiak village for more than 10 years. had won their trust. Without the relationship of trust between him and the people of Huiak village, I don't think I could have filmed Peeple's storytelling or the scene of digging potatoes and recreating a house made of banana leaves. Mr. Ito's contribution to this film cannot be expressed in credits such as "appearance" or "interpretation".

Q. How did you go about filming on site?

Finding the Mulaburi people who live a nomadic life in the forests of Laos, and reuniting with the Mulaburi people who hate each other because they are cannibals for the first time in over 100 years. These two were decided as major policies. After that, I went to Huayak Village, Doi Plai Wang Village, and the forest of Laos, and I proposed, "Can you shoot such a scene?" We repeated the process of reaching out to the local people and asking for their cooperation. I knew that if I could not film the life of the people of the forest in Laos, it would not be possible to make a feature-length documentary film, so I persuaded Mr. Ito, who was not very proactive, to hire a young man from the local village as a guide and go on a mountain climb. It was difficult until we left. It's true that I didn't understand the language, but Mr. Ito interpreted for me every step of the way, so I was able to understand the personalities and relationships of the Laotian Muraburi, and what they were saying with the intonation of their words and the nuances of their gestures. I know you are. So all I had to do was put my body in the right position and focus on getting a better shot. In the final scene where the Muraburi tribe faces each other, I expected some kind of chemical reaction to occur, so as a photographer, I just turned off the presence and quietly turned the camera.

Q.Did you direct as a director?

The Muraburi people living in Huayak Village on the Thai side speak Muraburi, but I asked Mr. Ito a question and asked Mr. Ito to interpret. I asked them to sing, and proceeded with documentary coverage. Of course, I cut everything, but when Uncle Fundoshi recreated a bed made of banana leaves in the forest, they asked me what they thought of Mulaburi in Laos. I was the one behind the scenes who pulled out the legend. In the middle of the trip, I decided to frame Ito-san, who was initially acting as an interpreter and coordinator, and make him the main character. When I did that, a sense of realism came out, as if the audience were witnessing the adventure. It can be said that it was my own application of Jean Rouche's cinema verité technique, in other words, intentionally putting the interviewer and the film crew into the frame to bring the rawness of the filming scene into the work. .

Unlike fieldwork in linguistics, when shooting a documentary film, you can't just sit there and wait for something to happen in front of the camera. I don't go as far as "directing" on site, but there are many cases where nothing happens without a certain amount of "guidance". For example, I knew from experience that at night, people in front of a bonfire would be in a different mood than in the daytime. I visited my bed. When Mr. Ito was talking to Mr. Bun in Muraburi, a memory trigger was pulled in Mr. Bun, and he suddenly began to excitedly tell the story of catching and eating a snake called "Kruol". People who normally use Lao have begun to speak Muraburi because of Mr. Ito's role as a catalyst. Because they are "guided" in that way, what they are reflected in "Mori no Muraburi" may not be their usual appearance. It can be said that it is another image of them that has been dug out so that it can be seen more clearly by drawing out through the intervention of the photographer and the camera.

Q. In the post-production after filming, I think there was a process different from the Japanese documentary, but what kind of work did you do?

I followed the field notes I wrote in the field and my own memories, and while I was in a state where I could understand what the Muraburi people were saying, I put together a summary for each sequence. Then, I showed the video to Ms. Ito and asked her to interpret what kind of conversation was going on. I was surprised to find that the conversation was almost exactly what I had imagined. So I cut it down to a version that was composed in about two hours. Next, I asked Mr. Ito to translate it in detail, and based on that, I edited it and brought it to completion. I managed to make it in time for the premiere screening at "Tokyo Documentary Film Festival 2019" in December 2019. After that, based on the Japanese subtitles, Ms. Ito and young people translated them into English, which were screened at ethnographic film festivals, anthropological film festivals, and indigenous film festivals around the world. Flow.

The Mura Buri people on the Lao side still live in the forest, but they no longer speak Mura Buri on a daily basis and are now Lao speakers. In the scene of the camp called Huai Harn, which is located in the forest after climbing the mountain for several hours and is the closest to the human village, the typical example is the fight between Mr. Kamnoi and Mr. Lee. It was happening, so it was all I could do to put it on the video. So, after having it translated, I found out that I was having that kind of conversation, and there were many times when I smiled.

Q. What do you think is the highlight of this work? What kind of people do you think will be interested?

As forest people and with a traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle, the Muraburi are different from those of us who live in cities, and from farmers such as the Thais who live in the plains and the Hmong in Zomia. I'm here. Mulaburi, who used to hunt small animals and fish in the forest when they were hungry and dig up potatoes and bamboo shoots to eat, have no intention of preserving them for the future. On the Laotian side, people are not involved in the money economy, where they plan and grow crops like farmers do, collect taxes on them, or convert them into money to purchase necessary daily necessities. Instead, they have a unique way of trading, taking what they collect from the forest to Lao villages and bartering it for things like rice and tobacco. Then there is the gift economy. This is also reflected in the footage of "Muraburi in the Forest", where all the food they got and the meals they cooked were shared equally with the people in the camp. This is the wisdom unique to hunter-gatherers who try to survive by sharing food with each other even when food is not available.

We have developed from farmers, producing extra things and accumulating them as surplus, storing it as wealth, and privileged classes such as kings, nobles, and wealthy people were born there, and skill groups It has a history of development and the establishment of a national system. The end result is the society of capitalist economy in which we live, and I thought that was the inevitable development of civilization. However, as discussed in the Anthropocene, the overuse of fossil energy has caused climate change, and nuclear power plant accidents have occurred due to huge earthquakes and tsunamis. In other words, we have come to realize that if we continue with modern values supported by an agricultural worldview and a capitalist economy, the entire human race will only go to ruin. At times like this, if you observe the lives of hunter-gatherers like Muraburi, it may sound like an exaggeration, but I think we can learn a lot from them for the future of humankind. I felt that the secret of another alternative way of life was there. For example, the muraburi are nomads and live a nomadic lifestyle so that they do not run out of the potatoes, fish, and fruits that are available on the spot. When you move to another place and come back after a while, the natural environment is recovering naturally. In Japan, we can learn from the hunter-gatherers about sustainable living in harmony with nature that has existed since the Jomon period. I think that the movie "Muraburi in the Forest" is a work that can throw something at all people who are aware of the problem that human beings cannot live as they are.

Q.Please give a message to the readers.

Especially since the beginning of the 21st century, I think that the changes in the global environment have become apparent. Volcanoes have erupted, typhoons and floods have occurred frequently, and natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis and wildfires have become commonplace around the world. Perhaps by God's invisible hand, a pandemic that seems to target the entire human race, which has increased too much, has spread, and we have not returned to our daily lives for more than two years. Under such circumstances, war broke out in Europe, and there was even talk of a nuclear or world war, and a large number of people became refugees. The world has become so hopeless that it makes me wonder what the development of human civilization has been until now. However, I felt a little relieved while filming the people of Muraburi and making this film. I realized that even without homes, electricity, gas, and electrical appliances, humans can live in abundance as long as there are clean rivers and forests. Seeing them and their faces made me realize that being surrounded by things is not so important.

Moreover, the people of the forest don't need to work to earn money, so they don't have to worry about tomorrow, they don't have to worry about tomorrow. there is When you're having a hard time at work or school, or when something bad happens in a relationship and you're feeling stressed, you suddenly think of Muraburi and take a deep breath like you're in the woods. If you try, you can distance yourself from the stifling modern society. And it makes me feel at ease knowing that I can throw everything away and live a nomadic life in the lush forest whenever I want. It's such a relaxing movie, so I hope people will come to see it just like when they think of going to the nearby forest to relax.

[Director/Cinematographer/Editor] Yu Kaneko

Filmmaker and critic. Associate professor at Tama Art University. His theatrical films include "Belgrade 1999" (2009), "Mneoism" (2012), and "Imperial" (2014). His recent work The Man Who Became a Movie (2018) was screened at the Tokyo Documentary Film Festival and the Tanabe-Benkei Film Festival. Produced "Garden Apartment" (2018) was screened at Rotterdam International Film Festival and Osaka Asian Film Festival. "Mori no Muraburi" (2019) is the fifth feature-length documentary film. Received the Suntory Prize for Arts and Sciences for her book, Eizo no Kyouiki. Other publications include "Frontier Folklore", "Literature of Foreign Regions", "Documentary Film Techniques", "Mixed Blood Retto Ron", and "Criticism of Joy". He has co-edited Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Jean Rouch: Transcendence of Visual Anthropology, and has co-translated books such as Tim Ingold's The Making and Alfonso Ringis' Violence and Brilliance. Editorial board member of the documentary magazine neoneo, program director of the Tokyo Documentary Film Festival, and member of the Institute of Art Anthropology.

[Synopsis] Huayak Village in Nan Province in northern Thailand is the largest community of 400 Muraburi people. The men go out to work in the Hmong fields as day laborers, while the women do side jobs such as child rearing and weaving. The Muraburi, who live in an illiterate society, are rich in folklore such as monsters and ghosts that they encounter in the forest. However, when Yuma Ito, a linguist, listens to the story and walks around, it seems that the Muraburi are afraid of another group living in Laos, calling them "cannibals." Ito and Kamera cross the border to search for Muraburi, who lives an old-fashioned nomad life in the jungles of Laos. In a certain village, I come across a scene where the Muraburi tribe comes down from their mountain camp and barters with the villagers. It was the girl Nannoi and the boy Lun. With the help of the locals, we entered deep into the dense forest. Can we meet the Muraburi people who are still hunter-gatherers? What are the problems facing forest people in the 21st century?

Muraburi Forest The Last Hunters of Indochina

2019 / 85 minutes / Murabulli, Thai, Northern Thai, Lao, Japanese / Color / Digital

[Director] Yuma Kaneko [Cast] Yuma Ito Pa Rong Kamnoi Lee Lung Nannoi Mi Bun Doi Pray Wang Village People Huayyak Village [Photography/Editing] Yu Kaneko [Local Coordinator/Subtitle Translator] Yuma Ito [ Publicist] Risa Toyama [Design] Haruka Miyoshi [Producer] Genshisha [Distribution] Omuro Genshisha [Cooperation] Institute of Art Anthropology, Tama Art University, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University [Web] https://muraburi.tumblr. com/https://twitter.com/muraburi https://www.facebook.com/muraburi

©Gensekisha

From Saturday, March 19th, theater image forum and other nationwide release

▼Related articles Visual anthropological documentary film "Mori no Muraburi Indochina's Last Hunters" Official interview film with Yuma Ito, a linguist who created the opportunity for ethnic minorities to meet for the first time. People", KOM_I and others recommended comments arrive Movie "Mori no Muraburi Indochina's Last Hunter" Special News & Scene Photos & Comments from Mr. Yuma Ito, the leading Muraburi language expert documentary film "Mori no Muraburi Indochina's Last Hunter" Released on Saturday, March 19, 2022 “Mori no Muraburi” – Movie

notebook-laptop

notebook-laptop